The strategic use of global trade regulations to further foreign policy is not new. Trade restrictions have been used for hundreds of years. From export duties on wool in medieval England, to the 1930 Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act in the United States, or the boycotts and sanctions on apartheid South Africa, countries have long used trade to further their own interests, make statements of principle, or impel changes.

As companies began outsourcing production and economies became more reliant on inter-country trade, these embargoes have become more disruptive.

While free trade agreements can take many years to finalize, and many more years to be ratified, in recent years we have seen trade policy changes happen almost overnight.

In addition, events like the abrupt political shifts in Venezuela, the contentious discussions around Greenland, and the short transition period between the finalization of the EU–UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement and its ratification, shows how quickly geopolitical relations can rewrite trade relationships, and disrupt logistics networks, creating a ripple of uncertainty across regions.

Commodities, Rare Earth Minerals and Semiconductors

The global economy’s dependence on a few countries for commodities, semiconductors, and rare earth minerals has created systemic vulnerabilities. The concentration of production in a handful of geographic regions and companies has become a critical supply chain risk.

This vulnerability has intensified as the global appetite for these concentrated resources has surged. Consider the numbers: China dominates 85% of rare earth refining, while only four firms supply 95% of the world’s semiconductor-grade silicon.

As a result, these materials have evolved into instruments of political power. Rare earths play a vital role in heat-resistant magnets, semiconductors, robotics, automotive systems, and aerospace applications.

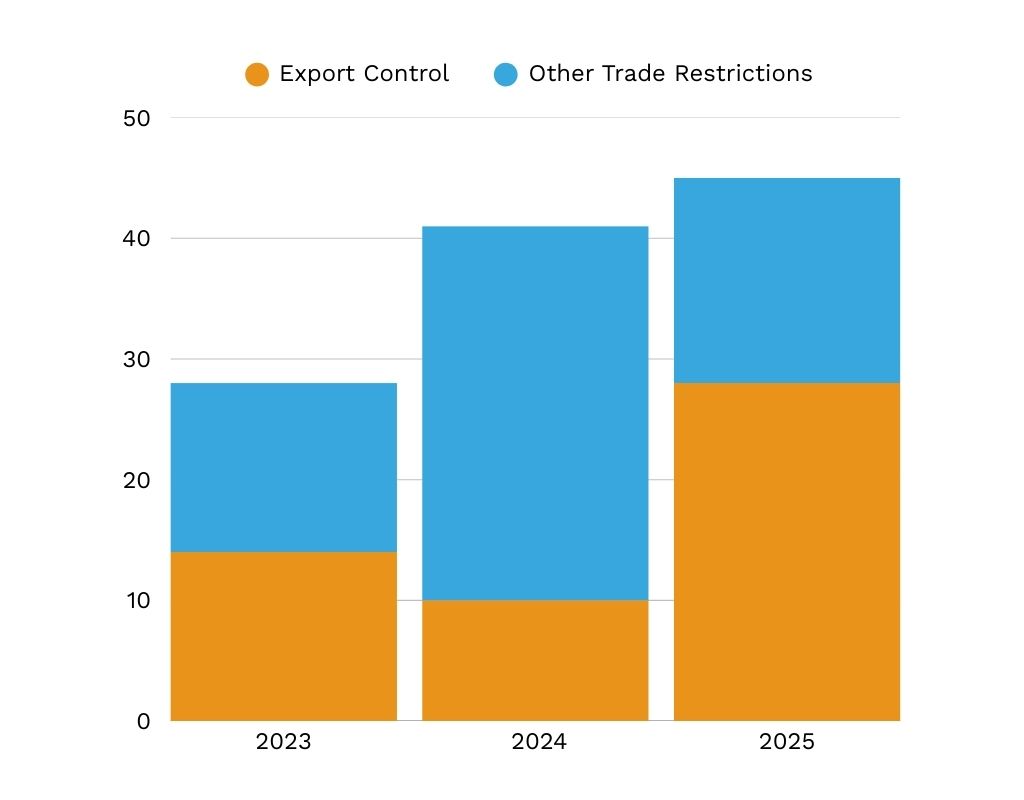

Export controls causing disruptions doubled from 2023 to 2025, and other trade restrictions increased by 167% in 2025 compared to 2023.

Figure 1: Disruptions to critical minerals due to export controls and trade restrictions

A recent example of this is the political tensions between Japan and China. This resulted in a rash of new restrictions in early January 2026.

China moved to restrict military-related exports to Japan in early January. The prohibition covers dual-use goods, such as aerospace engine parts, graphite materials, and specific tungsten-nickel-iron alloys.

Beijing tightened its grip further on January 8. Sources reported that Chinese authorities have allegedly stopped approving export licenses for rare earth materials and magnets destined for Japanese firms, regardless of industry. The timeline for reinstating these approvals remains unclear. If the freeze persists, Japanese production lines could face significant disruption.

Trade Agreements and Trade Blocs

In recent years, new trade agreements and trade blocs have begun reshaping the global economy, upending former alliances, and creating new ones.

Although the United States withdrew from the planned Trans-Pacific Partnership, Japan, Canada, Australia, and others moved ahead and finalized a new agreement, 2018’s Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP).

In 2024 and 2025, the BRICS group expanded from five members to ten, with the inclusion of Iran, Egypt, Ethiopia, the United Arab Emirates and Indonesia. The BRICS+ bloc, along with an additional ten partners, allegedly covers almost half of the world’s population.

The EU-Mercosur free trade agreement would create tariff free trade between the European Union and Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay. The bill has proved contentious, particularly with E.U. farmers, but if ratified, it would create a trading bloc encompassing more than 700 million people.

The European Union finds itself in a particularly difficult position, caught between protecting its industrial base from Chinese competition and managing a difficult trade relationship with its main security partner, the United States.

In 2026, the EU will need to balance transatlantic cooperation and targeted confrontation with China to avoid becoming the primary economic casualty in this great power competition.