The drought across Europe last summer and fall was one of the most severe ever recorded. In many parts of the continent, the magnitude of the heat and dryness was at levels not seen in hundreds of years.

The extreme weather resulted in massive economic cost with most estimates pegging losses at over $20 billion. Virtually every economic sector was involved with agriculture and livestock, transportation (primarily river transportation), manufacturing, and energy leading the way. The heat and dryness significantly depleted water resources including reservoirs, soil moisture, aquafers, and river basins.

Winter is a season that usually provides an opportunity for improvement and a replenishment of water resources. But this winter didn’t achieve its goals.

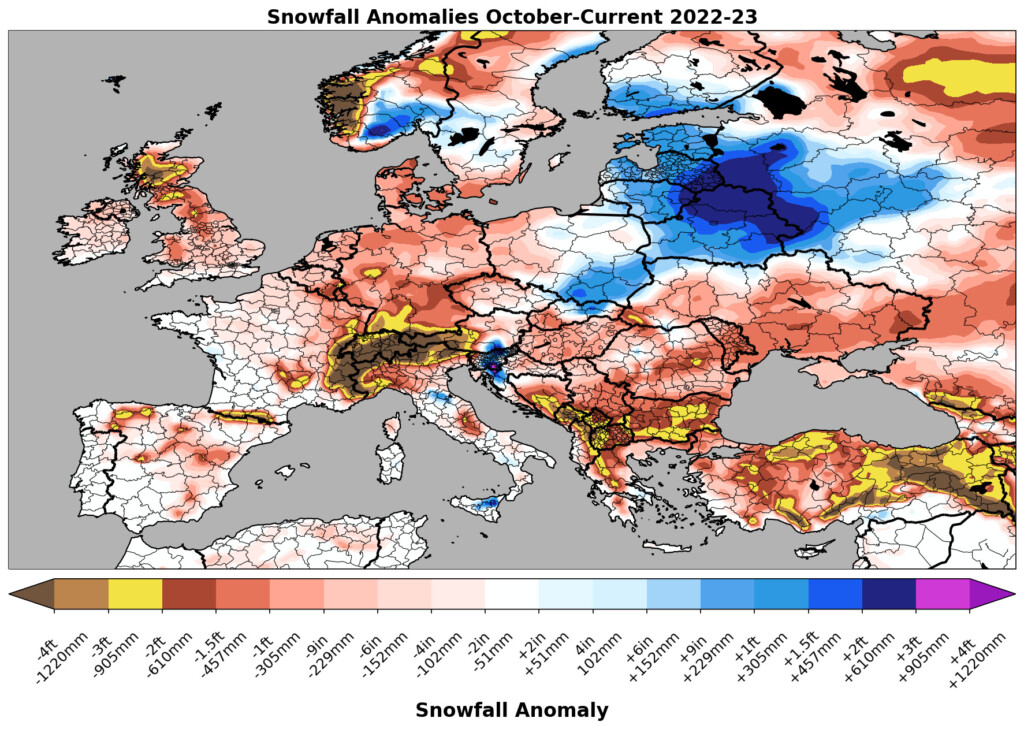

The December thru February period, which is defined as meteorological winter, was unusually warm and unusually dry. It was the third warmest winter in Europe since 2000/01. Precipitation, both rain and snow totals, were well below normal across most of the continent. The map below depicts snowfall anomalies during the winter of 20022-23 (October – March 10). Areas in blue/purple have received above normal snowfall totals this winter while areas in red/yellow/brown have received below normal snow accumulations. The most noteworthy area is the Alps. Snow totals in the Alps have been 3 to as much as 6 feet (90-180 cm) below normal.

The Alps play a crucial role in accumulating and supplying water to the continent. Moisture from the mountains (snow melt and rain systems) feed into the headwaters of the Rhine, Danube, Po, and Rhone Rivers. Additionally, mountain water provides irrigation for crops, fresh water for people and livestock, cooling needs for energy facilities, and a base for ecosystems far away from the mountains themselves. Hence, it is a key driver for social and economic wellbeing in Europe.

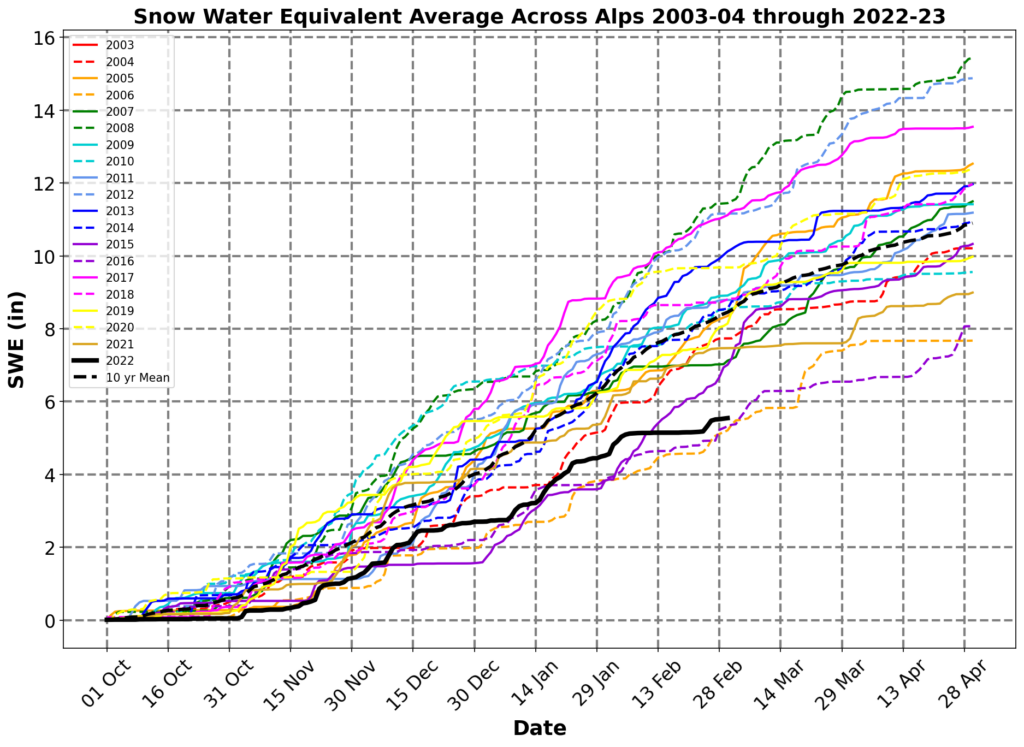

How does this year compare to other years? The graph below portrays the amount of water in the snowpack within the Alps from 2003/04 to this year. This metric is what we call snow-water-equivalent (SWE). When comparing the SWE in early March to other years, the current level is the 3rd lowest in the past 18 years. The bottom two were March of 2007 and 2017.

The low SWE raises concern about water resources going into the upcoming warm season. The lack of water reserves is not a guarantee of problems, but it does mean that Europe cannot afford any extended periods of heat and dryness this summer; frequent rains will be needed to keep up with moisture requirements. Abundant moisture in the Alps acts as an insurance policy for the summer season. This insurance policy is on the low end of the spectrum this year.

The favorable development is that in the short-term, the pattern across Europe is changing dramatically and the remainder of March will be very wet in all areas except for those along the Mediterranean. There are strong signals that the wet pattern will also continue into April. As a result, the situation will improve in terms of general water resources during the next few months. Heavy precipitation in the spring helps water resources but, in the Alps, much of it will fall as rain versus snow. Hence, any significant impact in the snowpack and resulting SWE in the Alps is not expected. This short-term moisture will help myriad issues in the short-term but not long-term due to the lack of improvement in the Alps.

As for summer heat/drought in Europe this year, there are no strong signals at this time. In other words, the long-range computer guidance does not have any strong signals for the summer. This is typical for this time of year (early March). For example, a year ago the computer guidance was not indicating any strong signs for heat and drought as of March. These signals didn’t began to show up and expand until the latter portion of the spring. The key time when the computer models have enough initial information to create a skillful forecast for the summer is April and May, when Everstream will be sharing further updates.