As we head into summer in the Northern Hemisphere, where most crops are grown, it’s looking less and less likely that there will be a cornucopia of crops during this year’s harvest. The next six months will be crucial in lowering food risk – but only if farmers everywhere can produce bumper crops this year.

Our climate and weather analysis shows that’s extremely unlikely. So, here are a few trends to keep in mind as we prepare for lowered food stocks and potential scarcities.

Weather patterns aren’t cooperating

The start of the growing season (spring planting) has been problematic in many areas and the weather forecast for the all-important summer development period is increasingly looking like it will be a summer of crop stress in many locations. With an already limited supply of crops, there’s little room for anything less than bumper crops – which, due to the weather, will be very unlikely.

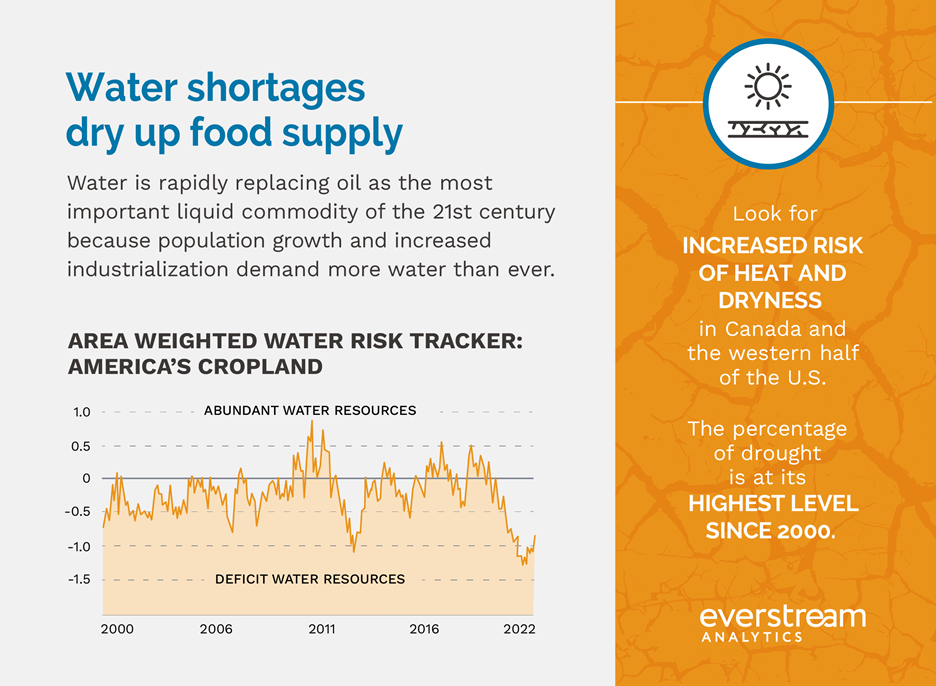

Drought levels in the Americas are at their highest level since 2000, due to a combination of La Niña and negative Pacific Decadal Oscillation (-PDO). Both La Niña and -PDO refer to the pattern of ocean surface temperatures in the Pacific Ocean.

We’ve seen La Niña conditions for the past two years, defined as sea surface temperatures that are cooler than the average in the central and eastern parts of the equatorial Pacific. These conditions, combined with the cooler waters near the U.S. West Coast and warmer waters stretching to Japan, defined as a -PDO (Pacific Decadal Oscillation), are key factors in ongoing drought and increased heat risk in western U.S. and Canada.

Of course, if farmers can’t cope with an ever-dwindling supply of water, it is unlikely that they will be able to produce the crops needed to feed the world’s population.

Agricultural insufficiencies won’t just lead to less food on the table, but also create a domino effect on other supply chains around the world. For example, you may not use soybeans in your operation, but soybean oil and soymeal are used in a myriad of products including packaged foods, biodiesel, and feed for chickens and hogs. In short, any crop shortage may threaten larger food supply chains around the world. Hence, the issues in the fields will reverberate around the world and threaten the global food supply chain.

Parched industries suffer shortages

Water has become one of the most important liquid commodities, nearly surpassing oil in its “value” across industries. According to the United Nations, 70% of the world’s freshwater is used for agriculture, while 19% is used for industrial purposes. Since water is used across farming, manufacturing, shipping, and more, water scarcity is now a global supply chain roadblock for many commodities, even if they seem unrelated. Agriculture, industry, and the global population must now compete for water.

Countries and industries that rely on hydroelectric energy also have found themselves squeezed as droughts reduce energy production. And, at the most basic level, water shortages have a direct impact on shipping, preventing barge movement and the flow of goods.

The continuing rise in industrialization, the continuous pressure that population growth has put on resources, and the effects of climate change mean that water has become more precious than ever before.

Technology promises hope

Climate patterns will continue to challenge farmers around the world, and businesses are noticing. The private sector invested nearly $88 billion in climate technology in 2021 alone. However, it will take time to find and implement solutions that can fully mitigate climate change concerns for farmers and suppliers.

In the meantime, there is technology that can help supply chains today. Businesses can use risk management insights to identify, forecast, and mitigate water risks. For example, Everstream’s water risk tracker identifies drought risks in a company’s extended supply chain network.

See more food risk factors in our infographic. Download now.