In a season when the world needed big crops, Northern Hemisphere weather did not cooperate. Conditions have ranged from mediocre in China/India to poor in the United States to disastrous in Europe. None of the major agricultural producers in the Northern Hemisphere had a “good” year when bumper crops would have been a major benefit to the world.

For relief, we look to the upcoming growing season in the Southern Hemisphere, where South America is the largest crop production area. Crops are planted in the spring (October/November) and harvested in the fall (April/May). A favorable growing season yielding big crops would be very beneficial for the world and help to ease the crisis next year.

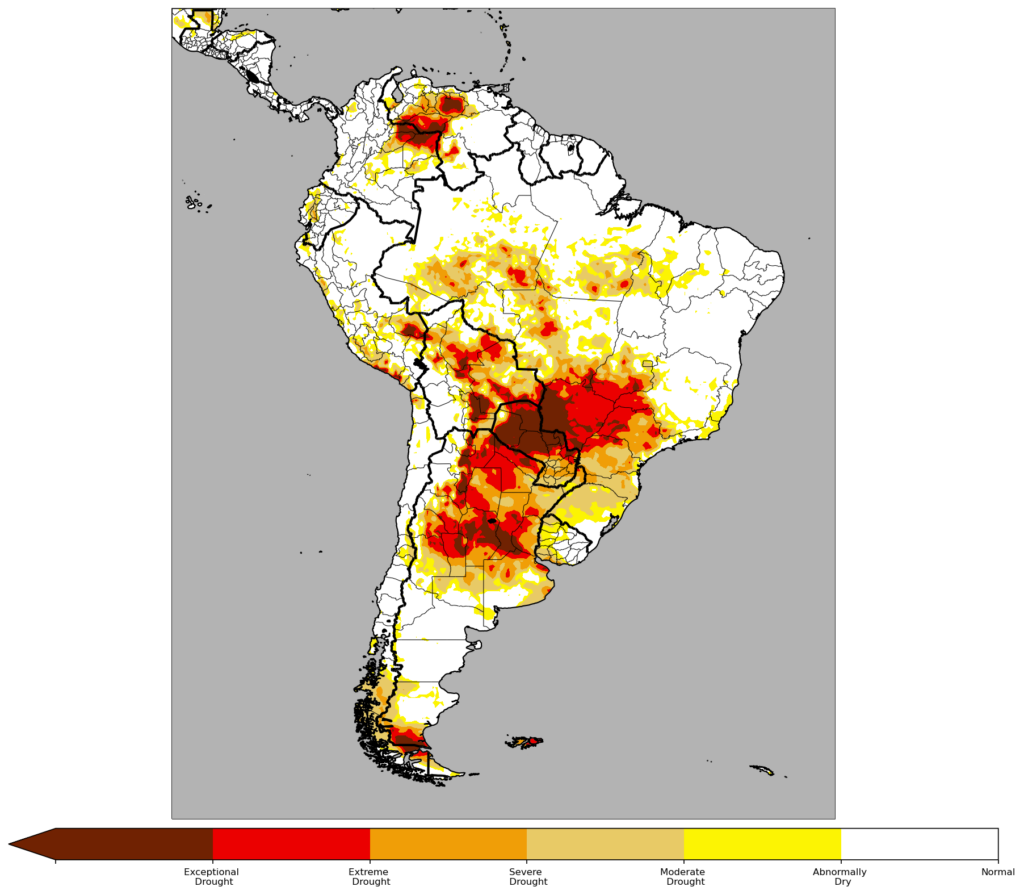

Unfortunately, some variables point away from the Southern Hemisphere season being a “bin buster.” First is the current dryness in South America. A significant portion of the prime growing areas (corn, soybeans, and wheat) in Brazil, Paraguay, and Argentina are currently in severe to exceptional drought conditions.

Figure 1: Early August drought levels showing a significant portion of prime growing areas in severe to exceptional drought conditions (source: Everstream Analytics).